Where Everything Fails, Art Takes Root

By Scott Edwards

It’s still raw and very much in a formative stage, but a surprisingly-large, and growing, community of artists is establishing the sort of presence in Trenton that was starting to feel unimaginable. More improbable still, it’s not a hostile takeover in the name of some short-term attention. Just the opposite, in fact.

The unemployed mill about Trenton’s East Hanover Street, creating the impression, upon first sight, that something’s about to happen. But it’s the middle of a prematurely-darkening Wednesday afternoon in February, so it’s clear, once the senses settle, that nothing will.

Parking meters flash beside a dozen cars. They’re the most modern detail of the block. Many of the decaying, three-story, brick and concrete buildings that flank the street haven’t been inhabited for years. How long before an abandoned building is boarded up?

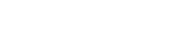

Squatting squarely in the center of the block is the 219 Gallery, appearing, in my dramatic mind, like a glowing bare light bulb dangling from the ceiling of a dark, stripped-to-the-studs ground floor in one of these shells of a building. Here, last September, SAGE (Stylez Advancing Graffiti’s Evolution) Coalition, a nonprofit artists’ collective, claimed the block as its own over the course of a three-day creativity frenzy dubbed the “Windows of Soul Project.” Its members treated every boarded-up window and door of nine buildings on the block as a canvas, creating elaborate, intricate murals on some and furnishing others with three-dimensional installations.

Where 72 hours earlier, there was rotting plywood, there are now poignant images and pink. The sheer quantity is overwhelming. You turn onto the street expecting nothing more than a shortcut to North Broad Street and then you’re confronted with this. And, really, confronted is the best way to put it. You may not stop that first time through, but you can’t not notice it. You can’t not ask yourself, What’s going on here? And then when you do finally stop, or slow down at least, your eye methodically scans from panel to panel because, ultimately, the meticulousness is the most staggering part of it all. Not one window or door was an afterthought.

The nearby residents and the mainstay millers were cautiously curious that first day. But by the end of the weekend, the session was an outright block party. Music echoed between the buildings, the smoke from barbecuing chickens drifted above the rooftops, kids giggled and darted among mobs of people who were no longer exclusive to the neighborhood, no longer exclusive to Trenton.

A slight shift occurred that weekend. After decades of neglect, nothing of any significance can change that quickly, that easily. But after it was all done, many of the people out on the sidewalks started to look up, sometimes even make eye contact. A few of the more invigorated ones offered a “Hey.” The block became a destination. Nearby government employees began wandering over during their lunch breaks. And, hourly, a car would pull up and someone would climb out and start snapping photos with his phone.

In that one weekend, SAGE, previously an unknown entity, proved its worth. “Everybody here respects what we do, from the fiends to dope dealers to just the regular, everyday folk because we don’t interfere in anybody’s lives,” says Will “KASSO” Condry, the organization’s founder.

It wasn’t just the locals who appreciated their tact. In a city loaded with—perhaps even suffocating under—nonprofits and government welfare agencies, SAGE suddenly appeared to make the dent that almost none of them could, with none of the funding or the connections. SAGE is grassroots not because it’s fashionable but because it’s the only way it knows how to be. Given the early results, the logic behind it feels like common sense. “As people start to get involved, we start to grow stronger,” says Leon Rainbow, a graffiti artist who’s among SAGE’s roughly-10-member nucleus. “It also gives the community and the people that come to our events and stuff more of a genuine connection with what we’re doing and a better understanding of what we’re doing.”

SAGE is, foremost, a community builder. It’s also the front behind which Trenton’s rapidly-growing band of emerging artists is uniting, for the first time, really. Its founding fathers, KASSO and Rainbow, especially, are bent on making this last. Progress is coming faster now. The two of them, though, have been at it for over a decade, painting and also planting seeds in vacant lots all over this cultural wasteland.

“My whole thing is there’s nothing wrong with making money. We live in a capitalist society. You have to eat,” KASSO says. “But at the same time, community building is something that is lacking. You build a community, you’ll make whatever you’re looking for after that tenfold.”

A product of their environment

The guys who came to comprise the core of the SAGE Coalition—and they all are guys, though an inexact number of women, in varying degrees of commitment, exhibit with them and help with the community outreach—passed in and out of each other’s lives frequently and unremarkably before they finally began to gel. Most are Trenton natives with the notable exception of Rainbow, a doughy, gentle guy who’s from San Jose, California. But he’s been in Trenton for so long, he may as well claim a lifelong residency.

SAGE, in the most technical sense, started with KASSO, who hails from the North Ward and wears a thick beard that projects a couple inches from his jaw line and spreads and contracts with his regular, broad smiles. It’s the brand under which he made hand-painted T-shirts. From there, he formed the SAGE Collective with three other graffiti artists. In varying combinations, they painted “unsanctioned” murals on abandoned buildings all over Trenton. But they weren’t random acts of expression. Or, at least, they weren’t only that. KASSO approached them as talking points. He wanted to open a dialogue among the people who lived around the murals, even if all they were discussing was the mystery of who made them. As far as KASSO was concerned, that was something.

“I’ve had deep conversations with KASSO where he’s telling me his life history, and it’s so different from mine, but it kind of doesn’t matter because we’re two artists who have a lot of the same interests,” says Aylin Green, a Lambertville, NJ-based artist and the membership director at Grounds for Sculpture, in nearby Hamilton, NJ. She painted a mural with KASSO and Rainbow last April in advance of SAGE’s annual “Soul of the Message” exhibition, in which her art was featured. “One thing he always says, which I think is really great, is, ‘Reach the world, but touch the ‘hood first.’ He has a commitment to this town, where he’s from. He has a really positive influence here.”

Gradually, over the last few years, the core members gravitated toward the Trenton Atelier, on Allen Street. It was founded in the ruins of a long-unused Roebling Wire Works distribution center by Peter Abrams, a Princeton, NJ, metalworker, sculptor and, as listed in his LinkedIn profile, the atelier’s “visionary leader.”

“I see this as a space for artists, for anybody, to come and do their work, no matter what it is. To take chances. To realize what they want to do,” Abrams says in a YouTube video promoting an open house at the atelier.

Kasso, Rainbow and Wills Kinsley, who turns bicycles into mobile sculptures, were among the first to come. Many of the others—Ahmad Shakir, a DJ; Byron “Black Collar Biz” Marshall, a rapper; and Graham Apgar, a digital artist—followed by invitation of one of the aforementioned. The open, informal arrangement is due as much credit for SAGE’s incredible diversity—visual artists of all shapes, musicians, DJs and poets have all been featured under the SAGE umbrella in the last year alone—as the easy receptiveness of the artists.

Abrams never bought the building. He took it over and asked the government to leave him be because he believed he was acting in the city’s best interest in creating a public space where, previously, there was only an abandoned warehouse on the verge of collapse. It didn’t. It came looking for overdue taxes, apparently, and when Abrams and the atelier’s occupants couldn’t cover them, they were promptly evicted last June.

But before they left, they came to realize that they were more creative together than they ever were on their own. KASSO has taken to calling the atelier refugees “Voltron,” as in the Transformer. “We come together like Voltron, you know,” he says, flashing the broad smile. Black Collar Biz, for one, categorized himself as a “standard rapper” before he set up a studio at the atelier. Lately, though, ever-stoic, he says he’s pleasantly drifting after falling under the influence of the UK-born, old soul-sounding tracks that Kinsley was constantly sharing with him there.

So as soon as word of the eviction was delivered, they organized what came to be known as the “Atelethon,” a fundraiser that was aimed at keeping them together. In less than two weeks, they created a 24-hour, interactive, many-layered art exhibition in the vein of “Art All Night” that they staged at the atelier. It raised a few thousand bucks, which was enough to cover their move to and the first couple months’ rent at the 219 Gallery, which they lease, along with a handful of studios upstairs, at below-market rates from the Trenton Downtown Association.

It’s hard to say how many comprise SAGE at this point. KASSO volunteers the size of the nucleus after I ask specifically about the ones who do the grunt work. There are lots of “minions” too, he adds. The 501(c)3-nonprofit status was established early, impressively, but they’re still in the midst of filling out a board and any kind of strategic plan. In the meantime, the few shoulder a disproportionate amount of the work.

But one of the reasons the infrastructure is slow to come is because SAGE seems to have become a beacon for a vast community of creatives that was previously lying in wait for someone to organize it. KASSO and his crew have been staging monthly exhibitions since they hit Hanover Street, and they’re booked through the rest of the year. All of those artists are networked with SAGE in some way, like Green, who’s not formally attached to the group, but who seizes an invitation—for a mural, a show, an outreach event, whatever—whenever she can make the time.

Basically, they make friends easily, and it comes even easier in a city starved for compassion and progress.

Trenton on the cusp

The near total lack of galleries means that the artists themselves, not curators or clients, are driving Trenton’s contemporary culture, which leaves it feeling raw, for sure, but also frenetic. Everyone seems game for anything because something’s better than nothing, and nothing is what there was for way too long.

When KASSO and Rainbow connected 10 years ago, they went to Philadelphia and New York City for opportunity and inspiration. Until KASSO started seeing Rainbow’s murals around the city—he tagged every one of them with his Web site, so he was easy to track down—he wasn’t even aware of another working artist in Trenton at the time. No one, at least, trying to make a living as one, like he was.

The mere idea of a living, growing culture in Trenton would have been said out loud only in an ironic way just a couple years ago. Until SAGE landed the gallery, nothing felt particularly cohesive to KASSO. There were flashes of promise, he says, but nothing truly sustained.

“Trenton has been saying for a while, I think, that it would like to revitalize through the arts,” says Green, who’s worked on the steering committee for Artworks’ “Art All Day,” a city-wide art exhibition and demonstration tour. “And my point to that is always, OK, that’s great. But you know what you need for art? You need artists. And, so I think that’s what’s happening, is that more artists are coming into town, getting to know each other and starting to work together and just kind of feed off of each other’s creativity and learn new things from each other. Even if they’re different things, just enjoy the fact that we’re here.”

Trenton is not making a miraculous comeback simply because SAGE formed. In fact, there are no visible signs of any comeback at all. To keep things in perspective, East Hanover Street still clings to its notorious reputation. Gentrification is not creeping in. If transformation was that simple, the aforementioned Artworks, a pillar in Trenton since 1988, would have pulled it off decades ago.

But SAGE is fast becoming the face of what is a highly-organic movement because it’s organized, it’s all-encompassing and it gives a damn about the city’s welfare, which endears it to all the right people, which includes the dope dealers as much as the councilpeople. At this point, nothing gets done without cooperation from both.

If the atelier brought them together, then Trenton Social, a South Broad Street pub that became the preferred hangout for local artists not long after its 2011 opening, exposed them to the need for coordination.

“I’m like, holy shit. You’re meeting people that’s doing shit. We’re not alone in this town,” says KASSO of his introduction to the Social. He painted, over the course of four months there, portraits of 26 Trenton Social regulars, including Shakir, who provided his soundtrack on Thursday nights.

“Beyond our group, it seems like there’s people starting to do shows regularly,” Rainbow says of the current climate. “We started getting the graffiti and the street art community going. Eventually, everything started coming together. And now there’s like different people that are starting to come up that are younger and doing their own thing.”

“There have been things going on here, but it has been maybe off the radar,” Green says. “And I think there’s this critical mass which is starting to form around artists and their activities here. I think [SAGE] are definitely at the center of it.”

KASSO’s big on consistency. He realizes that staging monthly exhibits is ambitious—he realizes now; he assumed it was common practice—but the frequency is what attracts the possibilities. In 2011, he drew “Garden Variety,” a showcase for local, unknown hip hop acts, to Trenton. He started hosting it right up the street from the atelier in another abandoned building, this one with no roof. He usually attracted 50 to 60 people and made just enough to cover the next concert. When he moved to a monthly schedule, attendance jumped and he discovered more people who were willing to collaborate, like TerraCycle, which hosted a concert. The lesson: Urgency breeds attention and, ultimately, yields results.

Once the board is set and a master plan put in place, the hope is to start fundraising and then to get into programming. SAGE will eventually move on from the 219 Gallery and East Hanover Street, not in a I’m-going-out-for-lottery-tickets-and-never-coming-back-kind-of-way that plagues neighborhoods like this one. KASSO’s ultimate design sees Trenton filled with East Hanover Streets, with chapters set up all over the city. Who’s to say where KASSO and Rainbow, Shakir and Black Collar Biz, Kinsley and Apgar will be or when they’ll be there. The only certainty is that they’ll be together. Actually, there are two certainties. The other is that they won’t leave under any ambiguousness.

“I can go around the corner, put up a [graffiti] panel and walk away,” KASSO says. “No one would ever know I did it. But if someone isn’t here to talk about it, to show people how to do it, then how successful were you?”